Love is everywhere: in films, books, stories, sagas, myths, not to mention in the masses of commercial products, from wedding rings, to flowers, to cards, to dating sites and apps. But how much of this can be explained by the biology of the brain – indeed should we even try?

Well, I will, with the risk of taking some of the intangible romance out of the concept of love, outline some of the biology of love.

All you need is love. Or so said the Beatles. But is it? Sorry I don’t want to put a downer on this from the start but what on earth is love?

“Come on Andy!” I can hear you cry; everyone knows what love is, don’t they? Well, no, we use the word often and we use phrases like that classic line from the Beatles as if love is universally accepted as a term. It is fuzzy, messy, misinterpreted in many ways, as many (if not all) romantic couples will tell you, and is used in wide and diverse contexts.

Types of Love

In fact, the Greeks famously defined eight types of love:

Philia: Affectionate Love. Philia is love without romantic attraction and occurs between friends or family members.

Pragma: Enduring Love.

Storge: Family Love.

Eros: Romantic Love.

Ludus: Playful Love.

Mania: Obsessive Love.

Philautia: Self Love.

Agape: Selfless Love. Love of humanity.

This shows us that there are many ways to define love. And the above will be familiar to all of us. I have also taken a different approach and in developing the SCOAP framework have applied an evolutionary lens to the Attachment Need which gives us another way to define the various aspects of attachment to others. These can be partly based on an evolutionary timeline i.e. some develop earlier than others but some of these also co-develop.

Lust: mating

Nurture: looking after offspring

Pair-bond: attraction to partner

Family: family and relations

Affiliation / Tribe: community, tribe, teams, and friends

Higher concepts: fantasy, imagination, future, self, religion

An aspect that comes with higher order functions, such as imagination and projection, is that we can then apply love to inanimate objects and build a sense of belonging and attachment to objects and desire for these (for reasons other than survival). But this is only an interesting side note at this stage and maybe a feature for an article for future articles.

But let’s return to what most of us think of when we think of the word love, and the focus in this feature – after all this feature is inspired by the approaching Valentine’s Day (despite my aversion to its commercialisation). And that is romantic love or “pair-bond” in the slightly less romantic terminology.

There has been an interest in romantic love and the brain almost as long as brain scanning become a more widespread part of cognitive psychology research. Though boiling love down to a few brain regions and neurotransmitters is something that some people still find offensive.

I remember an interview with Eric Kandel, one of the first neuroscientists and a Nobel Laureate, in which the interviewer asked him at the end of the interview whether the brain could explain love. The suggestion was that it seems ridiculous to explain something so powerful as love in simple terms of the interaction of chemicals in the brain. Kandel responded, in his wisdom, and with a big smile, that you can describe the processes, but the magic is something very personal.

Love and the Brain

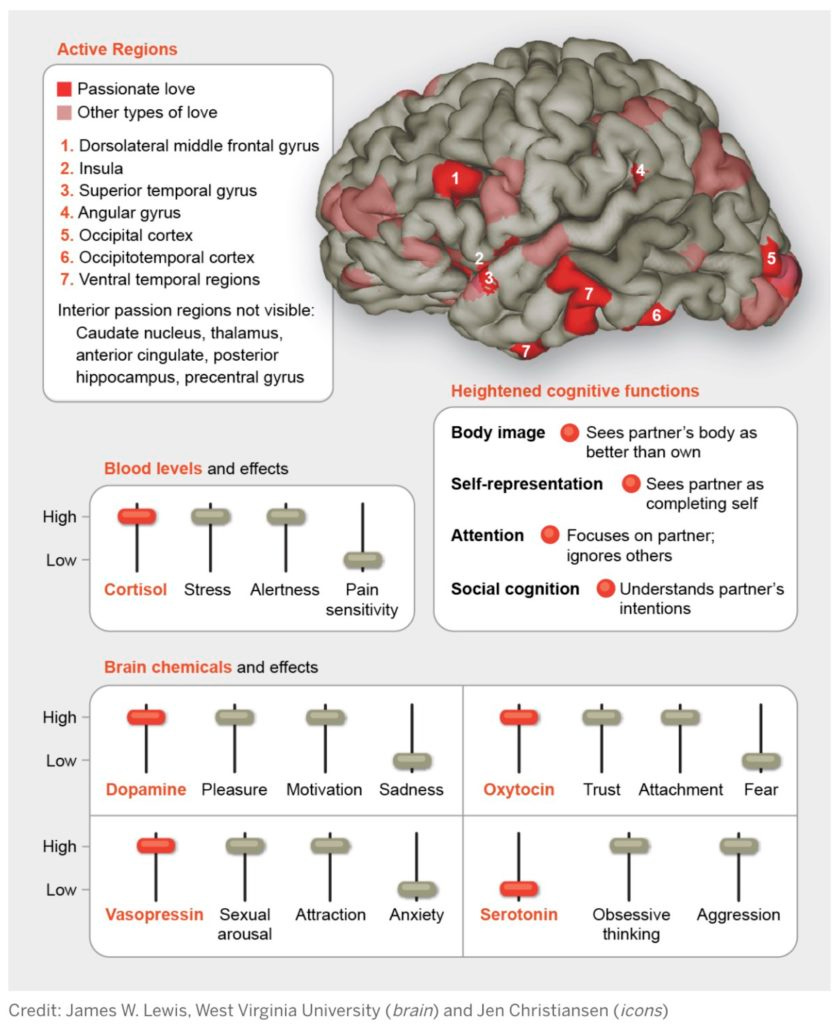

So, what has the last 22 years of research shown us since Bartels and Zeki first put couples in love in brain scanners and measured their brains in response to picture of their romantic partners?

Well, the first and perhaps most obvious is that high activation was seen in the Caudate Nucleus and Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA). Regions strongly associated with reward and reward circuitry. And so, the press release reads that love activates the reward centre - it is rewarding. This can also be taken a step further because early research into the reward centre also used cocaine to stimulate reward, so some media outlets also reported that love is similar to taking cocaine – or addiction. This is a big leap of interpretation with just these regions activating. But yes, love feels good. No surprise there.

Those of you who read my article on dopamine will also remember that the VTA is one of the primary centres for release of dopamine. As I wrote there, dopamine has thus been related to reward but is in fact is more related to significance and encoding learning. What is more interesting is the link with other chemicals released.

I have also reviewed oxytocin which is considered the attachment molecule extraordinaire. It is present in species that remain monogamous and is stimulated by all sorts of things considered romantic such as stroking, petting, and contributes to all things related to relationships. There is a dark side I outlined there also, because of its tribal bonding it can lead to us vs. them mentality.

What is more is that some research has shown that dopamine and oxytocin operate in tandem and in the right mixture can be a potent rewarding mix. So, this mix of dopamine and oxytocin goes some way to describe romantic love. But there is more: vasopressin is also released, and vasopressin is related to bonding, but it is also related more so to lust and sexual desire. So now we have the passionate love combination of bonding, reward, and sexual passion all combined into one package, with these three neurotransmitters going some way to explain these behaviours.

Other transmitters and networks can, however, explain also some other aspects of romantic and passionate love. Cortisol which I have also reviewed previously, though cortisol is considered by many to be a stress hormone it is also an activation and focusing hormone – some may say therefore that love is stressful, and it kind of is.

But the really interesting aspect is that serotonin levels drop which may sound strange. Serotonin is often associated with positive mood. Hence this combination of high cortisol and low serotonin can lead to wild mood swings and is also associated amongst others with obsessive compulsive disorders. So yes, being in love is also an obsessive-compulsive disorder - in the nicest possible way. Indeed, this is a feature of passionate love: obsession, compulsion, and wild mood swings from the euphoric to the depressive.

Other pathways that were first discovered by that initial research, and confirmed with later research, are also inhibited. The reward network is activated but other pathways such as the Prefrontal to Nucleus Accumbens or Nucleus Accumbens to the Amygdala seem inhibited. Why is this important? Well, these networks are also involved in critical assessments – so critical assessment is inhibited or in some cases, pretty obviously, completely shut down. This leads to not being critically analytical about our loved ones or the potential situations we are in, “Quit my high-paying job, move to a strange country, and get married to someone I have known for only three months. Of course, it’s a good idea!”

The Brain in Love

(from Scientific American)

This is also responsible for that inability to see anything wrong with one’s loved one – at least in those early throes of passionate love. Behaviours, physical features can all be ignored, or considered endearing, or just right – at least until the potent love cocktail beings to fade…

The diagram previously gives a nice summary of these regions and transmitters and their effects. We can also see that some regions are activated in different forms of love and attachment. And this now requires further analysis. How are the different types of love interrelated and does love fade or can it indeed be forever? The answer as with most things you read on these pages is more nuanced than a clear black and white.

But let’s first go back to our different forms of love and my evolutionary framework.

Lust

So, I class Lust, as do Aunger and Curtis, as the most primal form of attachment. Why? Well, a drive to procreate is the most primitive and important form for any species. No interest in procreating, no offspring, and no species, you die out. In fact, sadly one of the issues with Pandas and their survival is that they seem uninterested in sex…hence their endangerment.

Lust as an evolutionary drive is also not to be confused with human lust and human sexual fantasy – sexual fantasy is a higher order function using many higher brain regions to be able to imagine and construct these fantasies.

Fruit flies for example do not have the brain structures to create this sort of lust – they just have a drive to procreate. So, the primitive drive to mate is what the drive of Lust refers to. In the human being this is obviously connected to many higher order functions – but lust has been researched and is closely correlated to deeper brain regions such as the hypothalamus and sexual hormones such as testosterone.

Testosterone has been shown to increase sexual desire (in men and women) without an increase in attraction or attachment. Lust has also been shown to activate regions in similar ways to hunger such as the insula and striatum both of which can also be involved in reward processing and bodily awareness.

Mammalian Bonding

Enter then oxytocin – this is a feature of mammals particularly, and it is no coincidence or has, rather, driven the process by which mammals care for their offspring. Oxytocin I have outlined previously is responsible for many aspects of the maternal drives and maternal processes such as, stimulating labor, stimulating lactation in the mother and the transfer of oxytocin between mother and child increasing their bonding. Of interest is also that many of the newborn babies’ natural behaviours also stimulate oxytocin in mother such as suckling and stroking, and many mothers’ instincts also stimulate oxytocin in the baby such as the aforementioned stroking.

Stroking itself has also been researched: this has been shown to increase oxytocin between pets and owners. But of particular interest is that stroking at a certain speed activates certain skin receptors that trigger oxytocin release - a vigorous rub is not the same – which is why romantic couples naturally stroke and caress each other at a particular speed which is dictated by nature and our receptors in our skin and in our brains which is in turn related to hormone release.

Oxytocin is therefore in no short part responsible for nurturing behaviours in mammals including us human beings. Oxytocin is also responsible for our tribal affiliations, bonding us to others in our community and to our community ourselves. The downside to this is that it can also create and exaggerate us vs. them behaviours and respective aggression to the out-group.

So, these are the building blocks of different forms of love: the mother and child bond, the family bond, and the community bond. Then comes attraction and pair-bond which is also driven by oxytocin but combines with lust and the chemicals and brain activation patterns I have already outlined. This serves the function of attracting male and female to produce offspring and remain committed long enough to raise their children.

That last sentence may seem harsh but, from a biological and evolutionary perspective, couples only need to stay together for child rearing duties. This may not be strictly true as human beings have evolved in tribes, small communities which are dependent on each other for survival.

But it is also clear that human beings are not strictly monogamous, and many other species are also not. For example, field voles have been intensively researched also with respect to their oxytocin system and how this influences monogamous behaviour - but even the prairie vole long considered to be monogamous have been found to be not quite the angelic little critters researchers through they were.

Closer research showed that males and females of pairs were sneaking out for a quick bit on the side. The little rascals! But again, viewed through the cold lens of evolution this is an evolutionary beneficial behaviour ensuring greater diversity of offspring and better survival. Ahh the harshness of evolution.

Ever-Lasting Love

But before we come on to long-lasting love, which you may be glad to hear, does exist, let’s look at higher levels of evolutionary love.

Our higher order functions include functions such as projecting ourselves into the future, and having an imagination, and ability to think in abstract terms. Religion is just one such function – though some atheists and critics may see religion as unanalytical and illogical it is also clearly based on higher cognitive functions such as imagination and projection in space and time into, even, infinite space and time.

Only human beings have religion because only human beings have the brains able to use their cognitive functions in such a way. This means that in the case of love we can love abstract concepts such as an abstract God – of any sort I stress. But we can also love concepts, and project our love into the distant future or distant past – soul mates no less who have always and will always be together.

This abstraction can also be more down to earth and grounded in everyday objects - our brain’s mechanisms lead to us becoming attracted to objects and seeing these as desirable, but also as part of groups, and becoming attached to this group. This may be some well-documented things such as football teams: and research has shown that fans exhibit signs of love for their team, but also signs of religious fanaticism. It could also be to objects and brands. So yes, we do actually love brands, and objects, as much (or in similar ways according to brain chemistry) as we love our partners - don’t tell them though!

Ever-Lasting Love

So, with all of this, the question you may have is: can love be enduring?

Well, obviously it can we often love our children all our lives and many of our friends, but this is not the same as romantic love. Another thing that would go against enduring love is the idea of habituation – I am not just talking of generally making things into habits which happens to many things in life but the natural process within the brain of lowering its response to continual inputs.

If the brain, or a single neuron even, has a continual repetitive input, the response decreases over time. This feeling of getting a lower response to the same input is not just psychological it is biological – it is your brain responding at ever lower levels to the same input. This would suggest that living with a partner would habituate our brains – that reward centre activation that we get in the initial stage of romantic love will fade over time. Sorry, it’s just the way our brains are designed to work.

This would suggest that falling out of love or taking our partners for granted is the norm. But some people claim to be in love with their spouses or partners over long periods of time – is this just an expression or are they truly still in love with their long-term partners?

Well, this is what a group of researchers around Bianca Acevedo asked in 2012 and published under the title of “Neural correlates of long-term intense romantic love”. This particular study scanned the brains of 10 men and 7 women who had been married an average of 21.4 years and expressed that they were still in love with their spouses. What did they find?

They found similar patterns to those already outlined when shown pictures of their partners in contrast to other familiar faces including friends - their pleasure centres lit up. Looking at a picture of their loved ones was still activating their pleasure centres after an average of over 20 years! But what they also found in contrast to those newly in love was also strong activation of areas associated with bonding and attachment such as for one’s children. So, the pattern was of pleasure and deep bonding. What’s more, anxiety and fear centres were also inhibited as with those freshly in love.

Other research to support the habituation hypothesis, has shown that those in long-term relationships have a pattern that is similar to habit. This may sound negative, but it shows that the partner pathway becomes a deeply engrained pathway and default mode of operating – no bad thing in a long-term relationship.

So, the unromantic outcome is to make sure your partner becomes a habit – not quite the expression you want to put in your Valentines’ card. In fact, much relationship advice revolves around not making things a habit to return the spark of a dying or dead romance!

This may sound contradictory, but it is likely a balancing act – enough habit to make sure things roll along smoothly (and avoiding those wild mood swings with early passionate love) but continual reward and stimulus to keep things interesting.

The question we don’t know from those couples who do remain in love for over 20 years is, is this unique to those couples, their biology, or is it something that they are doing? Are some of us wired to be able to be in love for decades and others not? Evolution would probably distribute this across the population with some being unable to find a suitable partner and falling in and out of love multiple times and others finding their true partners for life. Are these people attracted to similar types: probably because the best was to predict long-term relationships is similarity!

Like Attracts Like

Similarity in what?

Well, in one unpublished study I know of, it was found that similarity of values was much more predictive of successful partner matching on dating websites than personality per se or interests. That makes sense - values are sacred things that we hold dear and contribute to our whole outlook on life. To have someone who doesn’t match your own values is unlikely to bring long-term fulfilment.

Of course, you readers will almost certainly be aware of my SCOAP model. And I would claim that being able to fulfil each other’s SCOAP is the best long-term predictor for a strong relationship as it is with just about everything else, we have measured. Can you make each other feel valued and special, can you give freedom and agency, can you keep each other informed and build a vision of life together, can you glow in the warmth of your relationship, and can you have pleasurable times together and enjoy each other. That is the recipe for a long and happy relationship.

Back to the opening of this feature. Love is many things but can be traced to the evolutionary development of the brain. We are built and wired to have different forms of attachment and love and these can be pretty neatly explained by activation of different neurotransmitters and hormones, and brain regions.

Romantic love is driven by a potent mix of reward chemicals, attachment, sexual desire, and combines with obsessive compulsive types of behaviours with a shutting down of assessment, and analytical parts of the brain.

Some people may wake up out of this to move on whereas others will build on this to build a long-term romantic attachment: to do this a deeper form of attachment needs to be built, some form of habituation, but continual reward also – and this must be aligned with values and your personal SCOAP. For if you can fulfil those, you will be aligned and fulfilled. And that is good place to be, indeed.

References:

Love

Acevedo, B. P., and Aron, A. P. (2014). Romantic love, pair-bonding, and the dopaminergic reward system. Mech. Soc. Connect. From brain to Gr., 55–69. doi:10.1037/14250-004.

Bartels, A., and Zeki, S. (2000). The neural basis of romantic love. Neuroreport 11. doi:10.1097/00001756-200011270-00046.

Bartels, A., and Zeki, S. (2004). The neural correlates of maternal and romantic love. Neuroimage 21, 1155–1166.

Beauregard, M., Courtemanche, J., Paquette, V., and St-Pierre, É. ́ L. (2009). The neural basis of unconditional love. Psychiatry Res. - Neuroimaging 172, 93–98.

Cheng, Y., Chen, C., Lin, C. P., Chou, K. H., and Decety, J. (2010). Love hurts: An fMRI study. Neuroimage 51, 923–929.

Diamond, L. M., and Dickenson, J. A. (2012). The neuroimaging of love and desire: Review and future directions. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 9, 39–46.

Fisher, H., Aron, A., and Brown, L. L. (2005). Romantic love: an fMRI study of a neural mechanism for mate choice. J. Comp. Neurol. 493, 58–62. doi:10.1002/cne.20772.

Graham, J. M. (2011). Measuring love in romantic relationships: A meta-analysis. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 28, 748–771.

Langeslag, S. J. E., and Van Strien, J. W. (2016). Regulation of romantic love feelings: Preconceptions, strategies, and feasibility. PLoS One 11. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0161087.

Mashek, D., Aron, A., and Fisher, H. (2000). Identifying, evoking, and measuring intense feelings of romantic love. Represent. Res. Soc. Psychol. 24, 48–55.

Mao, S. (2013). The Science of Love. Cell 155, 261–263. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.035.

Ortigue, S., Bianchi-Demicheli, F., Hamilton, A. F. de C., and Grafton, S. T. (2007). The neural basis of love as a subliminal prime: an event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 19, 1218–1230.

Wlodarski, R., and Dunbar, R. I. M. (2014). The Effects of Romantic Love on Mentalizing Abilities. Rev. Gen. Psychol.18. doi:10.1037/gpr0000020.

Xu, X., Brown, L., Aron, A., Cao, G., Feng, T., Acevedo, B., et al. (2012). Regional brain activity during early-stage intense romantic love predicted relationship outcomes after 40 months: An fMRI assessment. Neurosci. Lett. 526, 33–38.

Ted Talk

https://www.ted.com/talks/helen_fisher_the_brain_in_love?language=en

Oxytocin

Cariboni, A., and Ruhrberg, C. (2011). The Hormone of Love Attracts a Partner for Life. Dev. Cell 21, 602–604.Magon, N., and Kalra, S. (2011). The orgasmic history of oxytocin: Love, lust, and labor. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 15 Suppl 3, S156-61. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.84851.

Carmichael, M. S., Humbert, R., Dixen, J., Palmisano, G., Greenleaf, W., and Davidson, J. M. (1987). Plasma oxytocin increases in the human sexual response. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 64, 27–31.

Insel, T. R., Winslow, J. T., Wang, Z., and Young, L. J. (1998). Oxytocin, vasopressin, and the neuroendocrine basis of pair bond formation. Adv Exp Med Biol 449, 215–224.

Kemp, A. H., and Guastella, A. J. (2011). The Role of Oxytocin in Human Affect: A Novel Hypothesis. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 20, 222–231. doi:10.1177/0963721411417547.

Lawrence, R. A. (2004). Review of The Oxytocin Factor: Tapping the Hormone of Calm, Love, and Healing. Birth Issues Perinat. Care. 31, 157.

Evolutionary Model

Aunger, R., and Curtis, V. (2015). Gaining Control: How Human Behavior Evolved. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Habermacher, A., Ghadiri, A., and Peters, T. (2020). Describing the elephant: a foundational model of human needs, motivation, behaviour, and wellbeing. doi:10.31234/osf.io/dkbqa.

Lindholm, C. (2006). Romantic Love and Anthropology. Etnofoor 19, 5–21. doi:10.2307/25758107.