What a Sandpile and Your Brain Have in Common

A new paper outlines a foundational theory of the brain

When I first came across this theory in 2017 it resonated with me. Often on my writings and courses on the brain, I look at regions and processes in the brain and target this at coaches, trainers, or business folk. This may be how your brain replays practice during small breaks (so be sure to have more small breaks), how incubation leads to more insight, how our brain prioritises information (and sometimes the wrong information), and so on and so forth.

But some theories are big and seem to lack an immediate application but have large, wide, and fundamental impacts on everything we do. The “sandpile theory” is just such a theory.

I have called it the sandpile theory because that is easier to understand - the theory is more formally described as self-organised criticality. That sounds mighty grand, it is, but may turn some of you readers off.

So what is the Sandpile theory and why is it so important?

As I said, I first came across the theory in 2017 while writing material for my Brain and Behaviour Courses for coaches, trainers, and leaders. The theory goes back way further, specifically to Per Bak and Maya Paczuski’s 1987 paper when they coined the term self-organising criticality and Per Bak subsequently brought this to a broader audience in his 1996 book How Nature Works: the science of self-organized criticality. Per Bak himself had proposed this to a group of neuroscientists in 1999 according to the article in Quanta that introduced me to the model.

So, what is it about the model that is so appealing to me and why hasn’t it become more widespread in neuroscience circles - actually in all areas of life such as in big business?

A good question and my stimulus to write this article was prompted by some recent research pointing to the importance of self-organised criticality in brain disease.

The answer is that some theories or models are at a higher level - science aims to finds solutions to specific problems, the same applies in business. We want to know how brain cells work, which chemicals can change function, how dysfunctions are encoded in chemical or neuronal signatures, or ways to combat disease in discreet ways such as with chemical interventions or, preferably, with a new blockbuster drug.

This is just how we human beings are programmed. Big theories are sometimes big, but lack specificity - and yet this may be missing the point because everything may be following these rules and this may be influencing the whole function of our body.

Back to nature

Many years ago when I was first writing courses for trainers and leaders I put a base level on my diagram: it was labelled “the laws of nature”.

Why this? It is obvious: the laws of nature govern everything we do. At a fundamental level it is the laws of physics - as one physicist once told me, everything comes back to physics. This is true - but two or three or four levels removed to how we process information. We may be able to understand how a neurotransmitter such as oxytocin can stimulate bonding behaviours, but how the atoms of the chemicals bond together may be foundational, but too far removed from being practical.

But let me explain about natural patterns with ants and personality because this is one of my favourite stories.

The personality of ants.

Research into ants has shown that ants have, you may be surprised, different “personalities”. This is nice to know, bit is is not like in the humanised version of ants in movies such as Antz - but personalities there are and these differences and balance are important for effectiveness of a colony, their group decision-making, and their survival over time.

In the above study they documented that there are ants that are stable and accepting (putting human terms onto ants), when they find a new nest, they get on down to working – like an ant. They are what we would consider ants to be - they are our conscientious and hard-working ants.

But there are ants that don’t fall into this mould and these are more explorative. These will quickly get “bored” of the new nest and look for new nest locations even though they are not actually forced to. This gives us, in a simplified form, two types of ants but what is important is that this balance of explorative vs. hard-working ants ends up being balanced by nature.

The balance happens because if there are too many of one type of ant then the colony is less successful over time and therefore may risk being eradicated. If all the ants start running around looking for new nesting locations then none of the work that needs to get down to feed the colony and build the nest. But alternatively if the colony just gets on down to working then they may be missing on better nesting locations. Therefore those colonies with the right balance are more successful and will become dominant.

This mix of personalities therefore becomes evolutionary balanced. This is a principle of nature (or in my lax way of speaking a rule of nature) - and this is important because many business and many of us may try to violate these laws of nature and, indeed, we can do for a period of time, but only for a period.

Back to the Sandpile

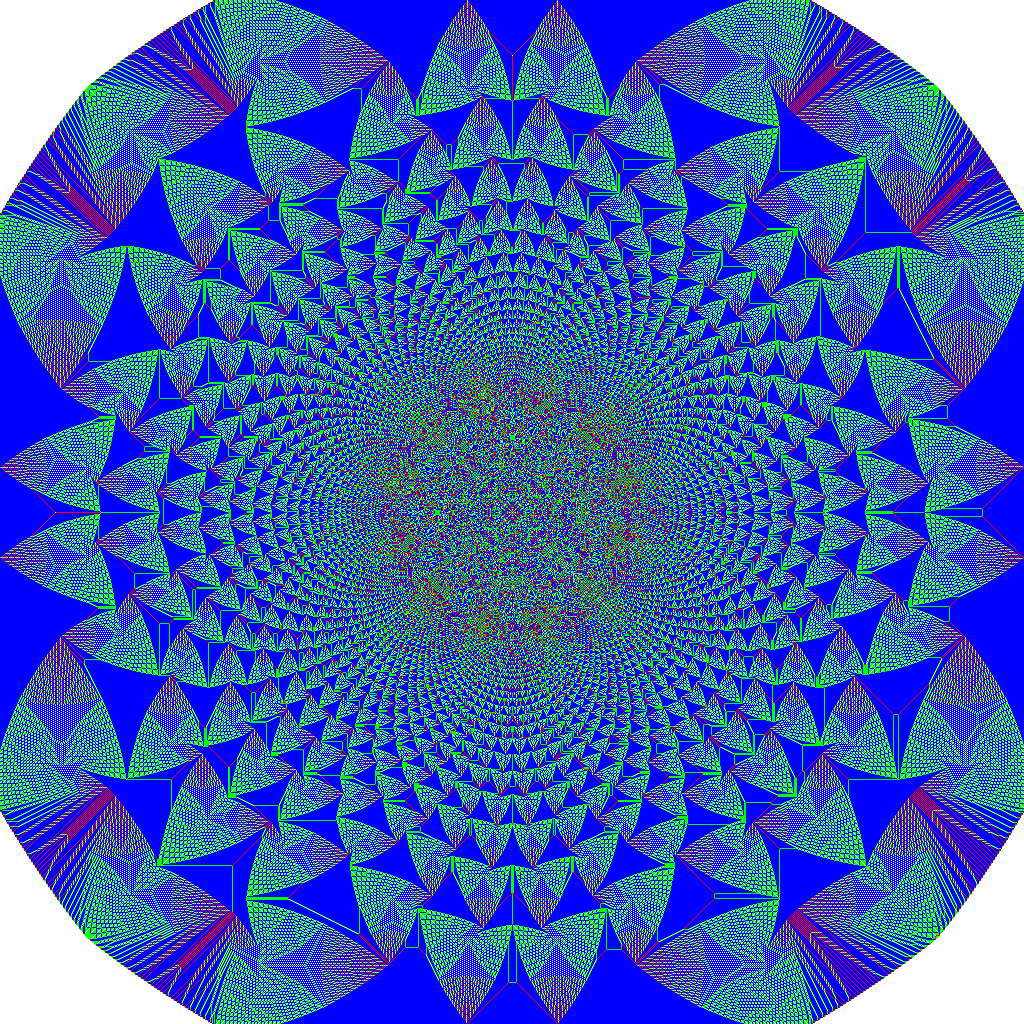

So let’s get the sandpile theory - why a sandpile? Well if you keep adding sand to a sand pile you will notice a few things. The sand keeps building up but it also regular falls away. As you keep pouring sand on a small sandpile there will be small mini avalanches, sand or land slides, as the pile self-corrects its form. This self correction is not cognitively driven, it’s a pile of sand after all, but correct itself it does. It corrects itself based on gravity and friction between sand grains.

It is self-organised. A sandpile does not need any central power to organise it’s mini landslides and help it form the optimal cone of sand. And criticality refers to those critical points of when the sand releases energy: first it builds up, reaches a point of criticality, and then releases.

What Per Bak and colleagues proposed is that this is a fundamental of all of nature. You can see these patterns everywhere, in earthquakes, in how populations of animals grow and shrink, in movements of swarms of animals. Self-Organised criticality seems to be an underlying principle of everything that happens on planet earth.

And what has this got to do with the brain?

Well this also seems to be how the brain operates and what he proposed to those neuroscientists in 1999 - the brain rides the wave of criticality building up currents and waves and then when they reach a critical threshold releasing them, and that gives us thought or builds up thoughts and action.

It also means that the brain operates best in this space of structure and order but also between flexibility and structure. When the brain veers away from this, its function becomes suboptimal, big avalanches may build up, and small avalanches don’t take place, or everything dissipates to quickly.

For example in a study in 2007 the researchers showed that after 36 hours of sleep deprivation the brain veered away from criticality. Normally, we would describe this phenomenon of sleep deprivation through energy systems and how different parts of the brain shut down or become less reactive - this is sometimes a very useful way to describe this: but it is not the foundational process - criticality is (or could be).

When we can walk the line of criticality our brains operate best, when not, operation is suboptimal or disrupted.

New research

My stimulus to write this short review was prompted with a new paper just out that focused on criticality in health, learning, and disease. This was authored by Keith Hengen an associate professor of biology at Washington University and Woodrow Shew a physicist and published in the illustrious Neuron.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to leading brains Review to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.