I’m stuck in the middle of multiple writing projects, with multiple insightful articles in the pipeline (not to mention the next chapter in my book) so this Sunday I’ll share one from the archives, originally published in 2020 but as, or more, relevant than ever.

Society is full of different groups of people, and we identify and belong to many of these groups. We can split along racial lines, nationalities, gender, sexuality, sports fans, political parties, the list is endless. But looking into our brains show how these groups can be the cause of many negative impacts in society.

I often show a short series of videos with babies when speaking on unconscious bias or giving workshops on the topic. They’re cute – infants from 3 months old doing behavioural experiments is really cute. You may wonder what is the point though?

Well, there is a whole lot of research done on infants. The reason is this gives us a strong clues as to what is “hard-wired” what are natural thinking processes of human beings that are present from birth - or not. We can make all sorts of assumptions from an evolutionary perspective, we can measure how adults act and respond, but in adults there is always the question of what is culturally inducted or not - what is learnt from our environment or not? Though children are not complete blank slates when they are born, they can learn aspects of their mother tongue for example, or recognise music they’ve heard in the womb, it gives us strong clues as to how brains are structured and operate right from the word go.

This also has buried some old-fashioned concepts such as children are born as blank slates and everything they develop, and all skills and behaviours, are learnt. This was the behavioural movement - Skinner being the most famous proponent who basically said everything adults did are due to operant conditioning: learning through reward and punishment in their environments. The cognitivists, on the other hand, argued that the brain comes equipped with certain predispositions and development trajectories. There were heated debates between these two camps in the 1960s and 1970s.

Cognitivism prevailed and we now know that we come equipped with predispositions that are 1. Human nature and 2. Individual.

But back to these cute little babies doing experiments and the good news and bad news. Let’s take the good news first.

In this particular set of experiments, these children are shown some simple scenarios with cuddly toys: in the first scenario a cuddly toy is trying to open a box but can’t open it. Then another cuddly toy comes along and helps the first one open the box.

Scene two then shows one cuddly toy trying to open a box and another one comes along and jumps onto the box and so makes it impossible for the first toy to open the box. This shows prosocial behaviour, helping, or antisocial behaviour, blocking.

So, which cuddly toy do the babies prefer? The one that helps or the one that is antisocial?

They are then given the choice of taking one of the cuddly toys, and almost always the babies choose the helpful toy. The prosocial toy. This shows that there is a natural propensity to liking and being attracted to prosocial behaviour. That’s good news.

I note that many people who see this first think that this could be influenced by the type of toy, rabbit vs, dog, or the colour of the t-shirt they are wearing. I stress that this type of experiment has been repeated multiple times, in multiples scenarios, using toys, cartoons, shapes, animals, and people. The results are always consistent. We have a natural prosocial bias, and this is naturally represented at a very young age. As young as three-months old. This makes sense we human beings are social creatures, as we will outline and strengthen in further articles in this issue.

From 60 minutes:

So far so good. Now these clever researchers have taken this a step or two further. We have now laid out the scene that there is a prosocial doggy and an antisocial doggy (a doggy in this example, in this case). This scenario is then extended: antisocial doggy is now alone on the stage and trying to open a box and can’t. Along comes another doggy and sees antisocial doggy. Should this doggy help the antisocial doggy or slam the box shut therefore seemingly punishing the antisocial doggy – pay back for its previous bad behaviour?

So, these two scenarios are played through: antisocial doggy gets a helping hand, and by another doggy, has the box slammed shut. Now if you think this through this is the same situation as the first situation but this time, we have more contextual information - we now know that the dog trying open the box is a bad doggy. So, what now happens? Which cuddly toy do the kids now choose if given the choice? Well, the answer is they choose the doggy that slams the box shut. The opposite to the first experiment. Why? Because the context has changed - and this is mirrored in adult’s responses also. We like to punish those antisocial individuals. Indeed, it suggest that humans think that antisocial individuals should be punished.

Fascinating! This shows us some of the roots of our natural human reasoning. Think of a movie and when the baddie gets their comeuppance, or a criminal is put in prison, and we see that justice is done. Again, I stress this has been repeated in multiple of experiments, in multiple different scenarios, and the results are always consistent. We do have a sense of justice and we do think that anti-social individuals should be punished.

Take a moment to think about this. This highlights that we are born with a sense of sociality. We immediately recognise prosocial behaviour, are attracted to it and also believe that antisocial behaviours should be punished. The primitive roots of justice are born and designed in our brains. We are born with a set of cognitive algorithms that guide this.

This is generally good news. Or until we look at another group of experiments with the same cuddly toys and consider how this can show the roots of societies and the worst sides of human nature simultaneously.

In this experiment the children are first given a choice of a snack. In this particular one it was gram crackers or cheerios, common cereals in the US. They are then shown cuddly toys who chose to eat either the snack they chose or the other snack. This is now creating an in-group. Note this is a pretty weak in-group (known as minimal groups). It is not as strong as an in-group such as nationality, or family, or supporters of a sports team that have many psychological bonding experiences. This is simply a cuddly toy choosing the same snack as you choose.

Now they re-run the same experiments I outlined above. A cuddly toy from the out-group is attempting to open the box. Another toy comes and helps them open the box or another toy comes along and slams the box shut. Now which cuddly toy do our innocent babies choose? Remember previously they consistently chose the prosocial toy without any context. When it was an antisocial toy, they chose the punisher. Now they simply have a toy that is a member of the "out-group".

Do they choose the prosocial toy as would be expected (as they toy hasn’t done anything bad)? Or do they choose to “punish” the out-group toy?

The depressing result is that the majority show a preference for the toy that “punishes” the out-group! Depressing, but true. This shows that in-groups and out-groups can be created almost at the drop of a hat and that these preferences immediately have an impact on how we treat those out-groups.

Now you may hope and note that this is only with cuddly toys and the punishments are not severe. They are not being hit or put in prison. But the reality is, the difference is striking. We have a prosocial preference in absence of any other information but as soon as we have more context, such as group belonging, our opinions can be changed dramatically.

This reflects the research into adults and how our brains process in-groups and out-groups. In fact, this concept us/them-ing is one of the best researched areas in psychology. The brain it seems is designed to build immediate in- and out-groups and the effects are widespread. And this us/them-ing:

is high speed – happens almost instantaneously

happens with minimal sensory input required

is unconscious and automated

is present In primates and babies

Note that these groups can be arbitrary, and we then often associate "markers" with these groups and imbue these with significance. In sports team these markers are intentional, for example with the colours and emblem of a sports team. Business brands do this also with their logos and corporate colours, but it could also be markers such as skin colour, dress codes, accents, or random arbitrary markers which become associated with an in- or out-group. Many of these markers do become intentional markers, symbols, and ones that imbue pride or disgust. In fact, we naturally want to build these markers and symbols of identification.

Belonging to groups can have positive effects but also negative effects.

The positive side of belonging to an in-group includes an increasing sense of belonging, team cohesion, feeling comfortable and protected with one’s in-group, and all the positive social aspects of this. This includes reduced stress, increased oxytocin, increased dopamine, and other opiates. We have increased empathy for our in-group which in turn becomes a virtuous circle increasing bonding and social support with one another.

Therefore, belonging to a group is linked to all sorts of positive effects in brain, body, and the endocrine system of human beings. We are designed to be in groups, or we are designed to be in in-groups.

The negative effects although can also be dramatic and severe.

Different responses to inspirational messages from the in-group and out-group - from Molenberghs and Louis 2018

Whereas we have more empathy for the in-group we have less empathy for the out-group. As in the above experiments that our cute little toddlers showed. Simply punishing the out-group for being the out-group seems hardwired. This is also related to other problematic processing of the out-group: for example, our levels of disgust are also higher for the out-group. We naturally see them as more disgusting and morally impure – this has been corroborated by brain scanning research which shows higher activation of the Insula which represents bodily feelings (review of Insula here).

In fact, political conservatism which is strongly associated with fear of the out-group and purity of the in-group are highly sensitive to disgust – and inducing disgust makes us more conservative – or more biased against the out-group.

This lack of empathy also means that we will punish the out-group with fewer qualms, but consider in-group’s suffering as much more severe. Something misunderstood by those on the political left is they think that a picture of a child suffering will cause conservatives to rethink their attitudes – this will only happen if it is in their in-group or looks similar to their in-group! Their brains cannot process this because if it is an out-group, their brains will not process this information.

An interesting piece of research hot of the presses by Inbal Ben-Ami Bartal from UC Berkeley has shed some new light onto empathy and helping with in-groups and out-groups. This is research done on rats who will help an in-group rat in distress but not an out-group rat.

What they noticed with neural responses is activation of the nucleus accumbens, normally considered our reward centre, activating dopamine strongly, showed a response in helping behaviours but not to the out-group. This suggests that one can feel some form of empathy but dopamine as reward and as motivation is what drives the actual behaviour to help or not. And that only activates with the in-group. This suggests building a collective is more important than building empathy (something misunderstood by the political left).

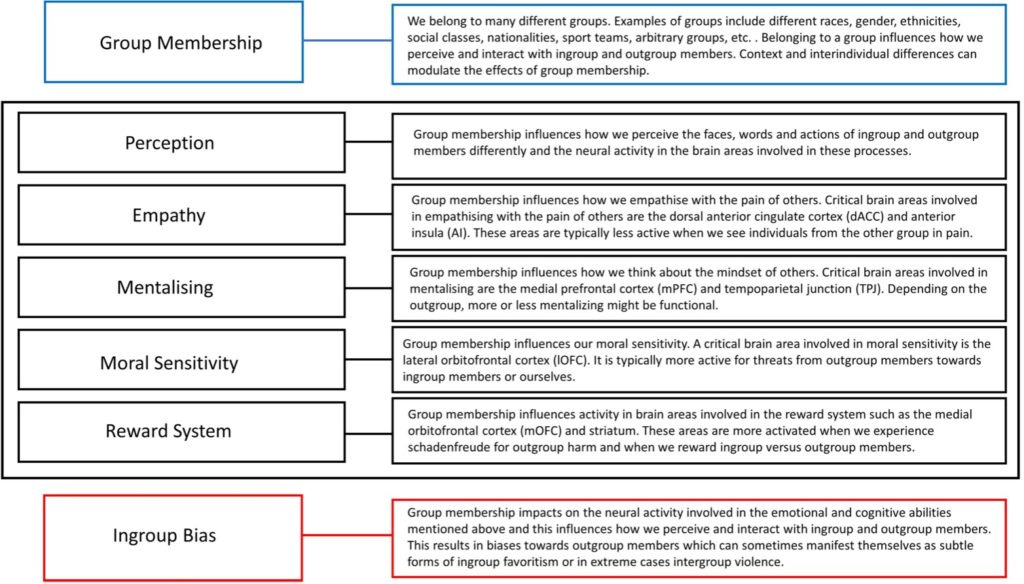

That said an excellent review of brain responses and in-group bias by Mollenberghs and Louis in 2018 does show differential processing. They report on differences in neural processing for:

Perception of faces, words, and actions

Reduced empathy for outgroup suffering

Reduced mentalizing for outgroup mindsets

Increased sensitivity to outgroup threats

Schadenfreude and rewarding others

Summary of constructs and results from brain imaging data. From Molenberghs and Louis 2018

Simply put, all the differences found in psychological studies are corroborated by imaging studies which show that the brain indeed does respond differently. When a football fan sees a supposed foul on their own player their brain processes this differently to the brains of the opposition fans. They are watching two different football matches.

This out-grouping can lead to the worst excesses and most evil actions of large human societies. It first starts with an out-group, they then become dehumanised, we speak of them as scum, animals, and from this it is only a step or two to the most horrific crimes. Admittedly, and fortunately, many of our human morals stop us making the next step or two, as do courts and political systems in the West. The next step or two lead to, at the worst extreme, genocide – though many of us may see the holocaust as the worst example of this – the Hutu’s and Tutsi’s in Rwanda, in the more recent past, show how in- and out-grouping along ethnic lines can cause the most horrific crimes.

This is important to note because there has been recent shift to the right in many western democracies and particularly to populism – populism appeals to those primitive instincts of the brain. These simple inborn “intuitive” instincts. And in-grouping and out-grouping is the favourite tool of populists. We have seen this recently in the US – more troublesome in the US is that though immigrants have come in for their criticism – the irony is not lost from a land of immigrants – and from second or third generation immigrants themselves. But with this in- and out-grouping within a country, there is danger that the country slowly starts to eat itself – when the communists were the out-group during the cold war there was clear unity. Now the out-group is just a different type of American. Very dangerous for a nation.

Alas, this simple mechanism that we see in those cute kids can also lead to some of our most pleasant experiences in life – those bonding experiences, feelings of warmth and acceptance, the joy of winning a trophy with a sports team, the shared memories and feeling of human connections that come with in-groups, must also be balanced by the extremes of making out-groups inhuman and the pain suffering and evil that can follow this.

In-groups and out-groups are guided by high-speed circuits, that are automatic, unconscious, require minimal sensory input, and are present right from the word go. Make no illusions this will not change – in a mild form this is a good thing but we need be aware and beware of strong out-groupings – to speak up and support those who are weaker.

As I write this an English footballer, Marcus Rashford, was racially abused for missing a penalty in the penalty shootout of the final of the European Football Championships - England lost. In this moment he was no longer an English team member, to some, but the member of a racial minority. A mural of Rashford in Manchester was vandalised. Sad – but the response warmed me more.

People of all colours and backgrounds spoke out about it – a million people signed a petition, and the mural was covered in messages of gratitude and love from people of all races and backgrounds. Showing that the racial abuse was the minority. This stand for equality is not to be underestimated. When a community stands up for an individual it brings them back into the in-group and shows the minority of racists that they are a minority. This weakens them and strengthens the community. This is known as the bystander effect and why this bystander intervention has been shown to be really important in these critical moments. And that gives me hope.

References

Ingroup Outgroup

Branscombe, N. R., and Wann, D. L. (1994). Collective self-esteem consequences of outgroup derogation when a valued social identity is on trial. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 24, 641–657. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2420240603.

Buckels, E. E., and Trapnell, P. D. (2013). Disgust facilitates outgroup dehumanization. Gr. Process. Intergr. Relations 20. doi:10.1177/1368430212471738.

Crocker, J., and Luhtanen, R. (1990). Collective self-esteem and ingroup bias. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 58, 60–67. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.58.1.60.

Dalsklev, M., and Kunst, J. R. (2015). The effect of disgust-eliciting media portrayals on outgroup dehumanization and support of deportation in a Norwegian sample. Int. J. Intercult. Relations 47. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2015.03.028.

Gonzalez, A. M., Steele, J. R., and Baron, A. S. (2016). Reducing Children’s Implicit Racial Bias Through Exposure to Positive Out-Group Exemplars. Child Dev. doi:10.1111/cdev.12582.

Hein, G., Engelmann, J. B., and Tobler, P. N. (2018). Pain relief provided by an outgroup member enhances analgesia. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 285. doi:10.1098/rspb.2018.0501.

Howard, J. W., and Rothbart, M. (1980). Social categorization and memory for in-group and out-group behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 38, 301–310.

Reicher, S. D., Templeton, A., Neville, F., Ferrari, L., and Drury, J. (2016). Core disgust is attenuated by ingroup relations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113. doi:10.1073/pnas.1517027113.

Kang, P., Burke, C. J., Tobler, P. N., and Hein, G. (2021). Why we learn less from observing outgroups. J. Neurosci. 41. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0926-20.2020.

Knobloch-Westerwick, S., Mothes, C., and Polavin, N. (2020). Confirmation Bias, Ingroup Bias, and Negativity Bias in Selective Exposure to Political Information. Communic. Res. 47. doi:10.1177/0093650217719596.

Shkurko, A. V. (2013). Is social categorization based on relational ingroup/outgroup opposition? A meta-analysis. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 8. doi:10.1093/scan/nss085.

Xu, X., Zuo, X., Wang, X., and Han, S. (2009). Do you feel my pain? Racial group membership modulates empathic neural responses. J. Neurosci. 29, 8525–8529.

Ingroup Outgroup and Brain

Ben-Ami Bartal, I., Breton, J. M., Sheng, H., Long, K. L., Chen, S., Halliday, A., et al. (2021). Neural correlates of ingroup bias for prosociality in rats. Elife 10. doi:10.7554/eLife.65582.

Bestelmeyer, P. E. G., Belin, P., and Ladd, D. R. (2015). A neural marker for social bias toward in-group accents. Cereb. Cortex 25, 3953–3961.

Bortolini, T., Bado, P., Hoefle, S., Engel, A., Zahn, R., De Oliveira Souza, R., et al. (2017). Neural bases of ingroup altruistic motivation in soccer fans. Sci. Rep. 7. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-15385-7.

Falk, E. B., Spunt, R. P., and Lieberman, M. D. (2012). Ascribing beliefs to ingroup and outgroup political candidates: neural correlates of perspective-taking, issue importance and days until the election. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 367, 731–43

Freeman, J. B., Schiller, D., Rule, N. O., and Ambady, N. (2010). The neural origins of superficial and individuated judgments about ingroup and outgroup members. Hum. Brain Mapp. 31. doi:10.1002/hbm.20852.

Han, S. (2018). Neurocognitive Basis of Racial Ingroup Bias in Empathy. Trends Cogn. Sci. 22. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2018.02.013.

Henry, E. A., Bartholow, B. D., and Arndt, J. (2009). Death on the brain: Effects of mortality salience on the neural correlates of ingroup and outgroup categorization. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 5. doi:10.1093/scan/nsp041.

Hein, G., Silani, G., Preuschoff, K., Batson, C. D., and Singer, T. (2010). Neural responses to ingroup and outgroup members’ suffering predict individual differences in costly helping. Neuron 68. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.003.

Huang, Y., Zhen, S., and Yu, R. (2019). Distinct neural patterns underlying ingroup and outgroup conformity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 116. doi:10.1073/pnas.1819421116.

Stallen, M., De Dreu, C. K. W., Shalvi, S., Smidts, A., and Sanfey, A. G. (2012). The Herding Hormone: Oxytocin Stimulates In-Group Conformity. Psychol. Sci. 23. doi:10.1177/0956797612446026.

Stallen, M., Smidts, A., and Sanfey, A. G. (2013). Peer influence: neural mechanisms underlying in-group conformity. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 7, 50. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2013.00050.

Wang, Y., Zhang, Z., Bai, L., Lin, C., Osinsky, R., and Hewig, J. (2017). Ingroup/outgroup membership modulates fairness consideration: Neural signatures from ERPs and EEG oscillations. Sci. Rep. 7. doi:10.1038/srep39827.

Review of Brain Imaging

Molenberghs, P., and Louis, W. R. (2018). Insights from fMRI studies into ingroup bias. Front. Psychol. 9. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01868.