Handbook of Your Brain in Business: 2. The High-Performing Brain 2.4 Your Decisive Brain

Handbook of the Brain in Business

The High-Performing Brain

Your Decisive Brain

Previous: Your Creative Brain

We have now looked at the High-Performing Brain in general, the Predictive Brain, and the Knowledgeable Brain, and lastly Your Creative Brain, all things that lead to highly functional abilities in all areas in life and business. But when it comes to business one thing often stands out above the rest - the ability to make good decisions.

Hundreds, and thousands, nay hundreds of thousands of books and articles have been written on the subject - and it is a big area (meaning this chapter is long). Nevertheless this is still but a summary, it is a chapter after all not a book. Let’s review.

The heart has its reasons which reason does not know.

- Blaise Pascal

Introduction

Decisions, decisions, decisions. As a coach I am often asked to help people with difficult decisions to make. This may be in big business contexts, in career decisions, or actual life or death situations as in one case with a woman undergoing cancer treatment.

But why are some decisions difficult and others easy? Indeed, some are easy, some decisions we regret, and some may change our lives. Then there’s those pesky emotions that may lead to all sorts of emotional turmoil. So, what is happening in the brain, and can we learn to make better decisions?

The answer, as always, is there is a lot going on in your brain, your emotions are probably your friend, but can be your enemy, and, yes, we can learn to make better decisions. But first let’s step back to an unusual and famous case that gave us our first clues to the brain and decision making.

A Metal Rod Through The Head

The story of Phineas Gage is one of the most told stories in neuroscience circles [1] and matches that of HM [2] (outlined in Your Knowledgeable Brain) as being standard stock in textbooks and told, time, and time again. I will repeat it for you non-neuroscience graduates, which is likely most of you, and despite having told it many times I still find it a fascinating and mindboggling. In addition to its gruesome fascination, it is also directly related to how we make decisions.

On September 13, 1848, Phineas Gage was working on the construction of a railroad near Vermont and was packing explosives with a metal rod (a tamping iron) into a hole in the ground to blast the rock. While doing this, likely a spark from this metal rod triggered an explosion just as Gage had inopportunely leaned over and was about to say something. This shot the tamping iron like a small rocket upwards and into his head as he leaned over with his mouth open. It entered above his mouth and shot under his cheekbone behind his left eye and up through the frontal part of his brain and exiting his skull at the top – landing 25 meters away according to accounts. Precisely the sort of thing that you would expect to kill a person outright instantaneously. Not so here.

Apart from being blown backwards and falling over he seemed to, amazingly, bizarrely, remain conscious and still have his wits about him. He was taken back to his lodgings in the nearby village of Clermont where he waited for a physician while conscious and reported coherently to said physician while being inspected. The case does boggle the mind because my mind imagines the damage that an unwieldy rod like that iron bar could wreak, but also the risk of infection and sheer trauma to the head.

However, despite all of this Phineas Gage survived losing his left eye and being left with considerable scars - though portraits of him with the tamping iron, that he kept as a souvenir, portray him as a handsome young man.

Probably precisely because of its gruesomeness this story has fascinated students and casual observers for centuries. However, from a neuroscience perspective what is interesting are the changes in his personality and the subsequent support to what was a new and novel idea of the concept of localisation i.e. that various regions of the brain have specialised functions.

The behavioural changes noted led to Gage becoming impulsive and aggressive and unable to hold down a job – though we’d probably expect a lot worse after having a hefty metal rod pass through your brain taking large chunks of brain matter with it.

These behavioural changes support the theses that prefrontal regions are involved in executive functions such as impulse control and also planning and related decision-making.

However, when we read the story in more detail, we also see that he would eventually move to Chile and take on a job as a stagecoach driver. It has been noted that this job would require considerable mental control, planning, anticipation, and memory. So, it would seem that whatever behavioural changes occurred he was later able to recover somewhat and take on a job requiring considerable cognitive resources, pointing to recovery and our old friend neuroplasticity.

Mind, and Body, and Emotions

Gage’s case has been used and abused by many a writer and the changes exaggerated for dramatic purposes. This brings us to the famed Damasio who in 1994 wrote the book Descartes Error [3] and proposed his famed concept of somatic markers describing how feelings are embodied concepts and influence out decision making.

The reason Damasio titled his book as such is that Descartes proposed what would influence Western thinking for centuries with the concept of duality: that the mind and body are separate entities. This is still present to a large degree in modern thinking and dual processes still guide many thinking models - sometimes this is useful and other times not.

Though Descartes was proposing a separation of mind over body another common duality is that of rationality vs emotionality. The quote at the top of this chapter by Blaise Pascal is one such indication: “The heart has its reasons which reason does not know.”

This emotional/rational duality is certainly still present in many realms of life – many people consider our rational mind and our emotions as two distinct and separate entities. And it is precisely this that Damasio challenged in his book, notably with the case of Elliot, a patient of his.

In the case of Elliot, we see a man that had been competent and successful in his role before being diagnosed with a non-malignant tumour on the frontal lobes of his brain. The subsequent operation left him with mild brain damage, as is often the case, and his personality shifted dramatically. Of importance for us is that his ability to make decisions at all levels from making simple lunch appointments to decisions about his job and indeed being able to hold down a job all took a hit. In fact, his decision-making went off the rails, he lost his job, couldn’t make appointments, and left his family (or his family left him) and he became destitute.

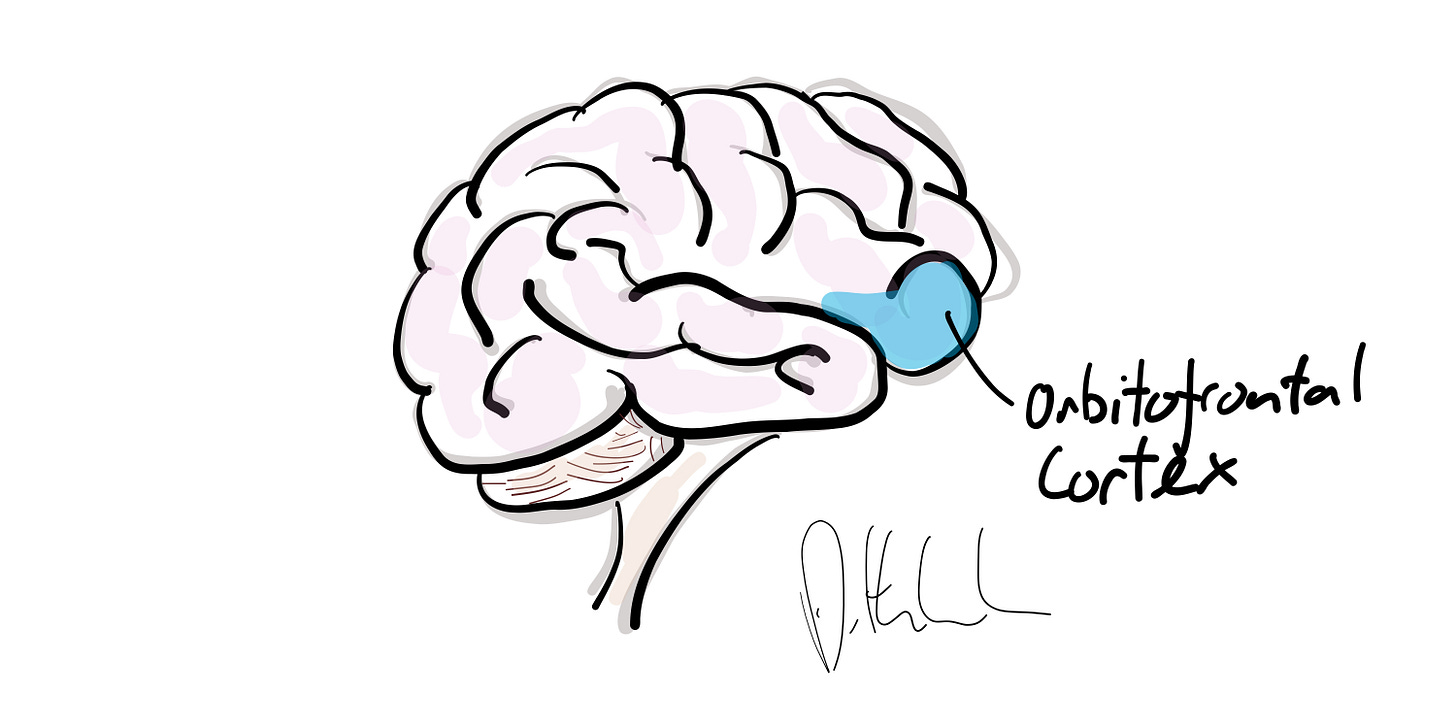

Damasio used Gage’s and Elliot’s cases to show how the orbitofrontal cortex is involved in decision-making. But specifically, not just in making decisions but also combining emotionality and reason. For example, in Elliot’s case Damasio argues that the lack of emotional input into the orbitofrontal cortex is what causes disrupted decision making.

For example, Damasio describes making an appointment with Eliot and how this was almost impossible. Why? Well, when there is a lack of emotionality, i.e. internal value assignment to dates, then the brain tries to work though all options without having any preferences, then this impedes decision making. Removing emotionality, or in Eliot’s case the connections to his emotional brain, makes decision making much more difficult.

So rather than emotionality disrupting decision making, emotionality contributes to decision-making by giving value assignments and hence pointing the brain, and ourselves, towards certain choices. This was the opposite to what many had thought at the time. At the time all emotionality was considered “bad” in decision-making.

Note that Damasio has been accused, justifiably in my mind, of massively over-exaggerating these behavioural changes of Gage and Elliot for his own purposes. For example, that Gage was able to do anything at all is amazing let alone hold on to a job driving stagecoaches which involves planning, thinking ahead and care for horses and passengers alike. This may point more towards the amazing effects of neuroplasticity – the ability of the brain to re-form and rewire (to a degree).

When Damasio wrote Descartes Error we were just at the beginning of the neuroscience revolution, imaging was becoming more widespread. Technologies have advanced and become much more refined since then and so have techniques and many an elegant experiment has been performed by countless researchers.

From the early 2000s we saw the rise of neuroeconomics researching the brain and economic decision-making[4]. Neuroeconomic research showed time and time again that the orbitofrontal cortex was involved heavily in economic decisions and value-based judgements [5-10] similar to what Damasio had proposed more than a decade earlier. So, it seems that the orbitofrontal cortex is a part of the brain, heavily involved in decision making particularly those that require value judgments i.e. taking into account our emotions and feelings or simply, “How much do I want to do that or want that product?”

Indeed, this is just how I have described the orbitofrontal cortex in my training and teachings - as a part of the brain that balances emotion and reason to come up with a decision. When you are fighting ration and reason this is the part of the brain that is going wild – “I want that ice cream”, “but it’ll make me fat”, “but it tastes good”, “it’ll rocket my cholesterol levels”, “yes, but it taste real good”, “what about the insulin spike”, “who cares its’s really tasty”,” oh heck, what if I take a walk”, “go for it that will justify that tasty ice cream”, “Ummm can you taste it already?”.

So yes, internal values, that are encoded as emotions guide decision-making – I will shortly give the latest view of the Orbitofrontal Cortex.

What the case of Elliot and our knowledge of the Orbitofrontal Cortex shows is that human decision making takes our emotional input to give a value judgement – therefore emotions, feelings, and values guide our decision-making process. This is not the cold rationality that many economists had assumed last century.

You may counter that high emotionality obviously draws us off track, and emotional and impulsive people make bad decisions, or that even rational people can make terrible decisions when highly emotional. That is also true – I will approach that topic a bit later also.

Is There Such a Thing as DQ (a Decision Quotient)?

On the same topic we do know that decision making ability requires considerable brain processing power particularly in more challenging decisions, particularly the type made in the business boardroom. Intelligence is also associated with higher cognitive control so we may also therefore, logically presume that higher IQ correlates with higher decision-making ability.

Not so according to Moutsasis et al. [11] based on a paper published in 2021.

In this they measured 830 young adults, between 14 and 24, on a battery of 32 decision-making tasks and tracked this over time. This was combined with various other measures, and brain scans of a subset of 349.

From this they discovered that there seems to exist a decision ability which is independent of IQ and that this is stable over time – in this study over a period of 18 months. What’s more they identified key influencing factors and brain measurements of this. I will come back to this later. But this shows that intelligence itself is not related to ability to make good decisions and that this is indeed an independent variable – something businesses should pay attention to. Note that I do not know of this ever being measured in the corporate world.

So, emotions are essential for decision-making, and we also now know that decision-making ability is independent of IQ. This already breaks some assumptions of decision-making. The next is that we know how we make decisions.

We looked at the flash of insight in the last chapter, when a solution or idea pops into mind and we get a sense of relief and reward as an idea comes into our consciousness. I also described the two-cord experiment in which almost all participants failed to identify a clue that triggered their flash of insight.

Our Ignorance

Does the same apply to decision-making? How aware are we of our decisions and the reasons for them? Not very, is the answer, and maybe our conscious decisions are just our way of justifying what the brain has already “decided” to do. This is what Libet showed in a novel experiment way back in 1983[12].

In these experiments he gave participants simple decisions to make (move a finger) and recorded their brain activity with EEG while doing this. The participants noted when they decided to move, and we would expect there to be awareness of decision coupled with brain activation and then movement. But the unusual thing was that there was heightened activity before making this conscious decision – what is now known as a readiness potential. This suggests that our brain is deciding and we, or our consciousness, is following with a short delay.

This was a surprise at the time and showed two things: one that our brains seem to operate in advance, or that our consciousness was behind our brain but two, this questioned the concept of free will – if the brain is deciding in advance and we are merely parroting our brain’s response do we really have free will?

In psychology this is known as confabulation. Confabulation is the concept that we post-rationalise or give reasons that are essentially invented, or what we see as reasonable cause, for our insight, ideas, or decisions we make. This is precisely what we saw in Meier’s two-cord experiment.

But this was not new in 1984, a landmark paper by Nisbett, before Libet’s experiment, in 1977, outlined the multiple ways that humans tend to post-rationalise and confabulate reasons for decisions. The title says all we need to know “Telling More Than We Can Know: Verbal Reports on Mental Processes”. Here the abstract:

Evidence is reviewed which suggests that there may be little or no direct introspective access to higher order cognitive processes. Subjects are sometimes (a) unaware of the existence of a stimulus that importantly influenced a response, (b) unaware of the existence of the response, and (c) unaware that the stimulus has affected the response. It is proposed that when people attempt to report on their cognitive processes, that is, on the processes mediating the effects of a stimulus on a response, they do not do so on the basis of any true introspection. Instead, their reports are based on a priori, implicit causal theories, or judgments about the extent to which a particular stimulus is a plausible cause of a given response. This suggests that though people may not be able to observe directly their cognitive processes, they will sometimes be able to report accurately about them. Accurate reports will occur when influential stimuli are salient and are plausible causes of the responses they produce, and will not occur when stimuli are not salient or are not plausible causes.

This is just as relevant today as it was in 1977 and despite this research being over 50 years old the concept that we post-rationalise and have little access to our decisions has not really passed into the business world. I still meet many business folk and executives who are sure of their rationality or reasons for their decisions. The problem is that overconfidence is a pretty good recipe for bad decision making.

Defining Decision Making

The above already redefines how we should think of decision-making but we haven’t done something we absolutely need to do: we haven’t actually defined decision-making. And that could also be a problem because we may be speaking of very different things when it comes to decision-making.

Here are some sample definitions to get us started:

Decision making is a fundamental cognitive process of human behavior by which an option is selected among a set of alternatives based on subjective preferences [13].

Decision making can be defined as the selection of a course of action among options [14].

Decision making involves the process of selecting a course of action from a set of alternative options and typically involves: (a) multiple competing options, (b) a set amount of information, (c) a specified timeframe, and (d) some level of uncertainty [15].

Decision making is required for behaviors ranging from simple movements to the complex consideration of multiple alternatives and reasoning about distant future consequences [16].

Decision making involves coming to a judgment about which of a number of potential options is best at a given time. Making effective decisions involves: (1) identifying alternative courses of action, (2) identifying possible consequences of each action, (3) assessing the probability of each consequence occurring, (4) choosing the best alternative, and (5) implementing the decision [17].

Based on the above definitions any of the following could be defined as a decision:

Getting out of bed

Having a coffee

Starting to work

Choosing words in writing this

Deciding where to hit the ball in a tennis match

Deciding what words to use in a conversation

Deciding on a strategy for a negotiation

Deciding on resources allocation for the next year

Deciding on financing options for an acquisition

But in many business books we may only consider the final three as truly business decisions. But, and this is important, from a biological perspective, all of the above are decisions. They all involve activating something or not activating something be that biologically, to initiate a behaviour, to achieve something, no matter how small or trivial it may seem.

Given this broad range of decisions, as above, I distinguish them based on their underlying mechanisms and this gives us a new way to think of decisions and therefore how to impact them.

I have used sports analogies a number of times as the parallels to high-performance in business are popular and similar in some ways. In sports and business and everyday life we often have to make decisions, choose options, or engage in courses of action in very short time periods, fractions of a second.

In sports we often speak of quality of decision making – remember I spoke about the Athletic Intelligence Quotient in the High-Performing Brain which includes decision-making ability. But when we talk of decision making in a game of soccer, this is very different to what many of us may assume happens in business. The reason is that it happens almost instantaneously – precisely that pattern recognition that I wrote about in Your Predictive Brain.

This type of decision making is different to for example deciding on corporate strategy because there is little conscious deliberation – it has to happen in the moment, in fractions of a second. Yet this type of decision making is also present in business, when in a negotiation, negotiators need to respond in the moment to how their counter parties engage, and many decisions that come at individuals in business need to be responded to immediately.

Another interesting nuance to these decisions in the moment is that it may not just be balancing good outcomes but restraining oneself that can lead to better decisions. At least in the context of football.

A study by Takahiro Matsutake of Osaka Metropolitan University in Japan [18] measured brain waves with EEG of 14 collegiate soccer players compared to 7 non-soccer players as they made decisions to make a pass based on whether they thought a pass was available (they had to tap a bar with their foot to simulate the soccer movement).

They found the obvious firstly — the soccer players were quicker and more effective at making these decisions. So far nothing out of the ordinary. However, what was surprising is that the brain wave patterns of the skilled footballers were of showing inhibition — in other words it seems that suppressing other automatic responses is key to making the best decisions. Obviously sometimes you need to pass, and at other times not passing is the best decision and this requires rapid inhibition.

This is interesting and could apply to all areas in life - sometimes suppressing the obvious, or suppressing a natural reflex can lead to better decisions.

So, good decisions are as much about deciding what to do as they are deciding what not to do.

It is probably clear to all of us that this decision-making in the moment is very different to analysing strategy before a game or match has started. The same applies to the business world.

If we take a quick detour to evolutionary development of behaviour we also come to a clearer way of categorising decisions and the biological mechanisms behind these.

On writing about and researching our SCOAP model I read a book on the evolutionary development of behaviour by Aunger and Curtis, Gaining Control [19]. This I found was a fascinating journey through the development of behaviour across all organisms including human beings and highlighted the similarity of certain behaviours across species and how to categorise them. They called these behaviours BPU’s short for Behavioural Production Units. This also neatly matched to the evolution of the brain and various brain regions. There was however, one problem.

The problem was that the terminology and ways of describing behaviour diverged completely from how we were describing behaviour through psychological needs. Not a problem you may think because Aunger and Curtis are focusing on biology, and we are focusing on psychology albeit neuropsychology. However, this is not true, because a basic premise of needs theories, and particularly the SCOAP model, is that these drive behaviour. Aunger and Curtis seemed to make complete academic sense as did the SCOAP model yet, they diverged completely in descriptions. That is until it all clicked into place.

It clicked into place when I realised that the SCOAP needs could be seen as broad buckets of behaviour in which all other behaviours and needs would slot. A primitive behavioural drive is also a biological need, and this also makes it a psychological need.

But what has this got to do with decisions? Well, all decisions are choices of behavioural options and evolution guides our behavioural selection and therefore taking options, let me explain.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to leading brains Review to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.