It seems like a no-brainer. In a competitive world, focusing on competitiveness is a good thing. But the issue is that collaboration is just as, or more, important. So how much competitiveness is good within and for a business?

"We need to focus, we need to be competitive". It’s the sort of thing you can imagine any senior executive telling their subordinates and peers. Sure, every business is in a competitive market, but the funny thing is this idea of competitiveness is a lot less important than you may think. In 2012 we started collecting data on our newly developed SCOAP-Profile. In this we had some items on competitiveness, specifically performing better than colleagues. This was not a random idea but based on plenty of research that showed how we compare ourselves to others constantly and that some aspects of self-esteem are likely strongly related to this comparison to others. Being better, being the best. What did we find?

What we found was that of all the items in the survey this one performed worst. Actually, it was junk. Well, it wasn’t junk it did show which people valued competitiveness. Other research has shown this to be 30-40% of people. This matched our results. 30-40% of people rated this highly and the rest? They rated this as the least important factor in their experience at work. What does this mean?

It means that the majority of people in the workplace do not want to be necessarily better than others. But we also noticed that they wanted to perform. So, there is strong tendency to want to perform, but not to out compete peers. Now you may think these may be lowly workers, but the population group we assessed was generally educated professionals in multinationals, mostly with relatively high-raking roles i.e. mostly working for various multinational in corporate centre and leadership functions.

Many of them were classed as high-performers and included various talent pipelines - dependent on organisation. So, this group would be exactly the group we associate with being competitive and driven people. I do stress most of them were driven but it’s just that outdoing others was the least important factor in their experience at work

This now raises a paradox - we like to be competitive, but most people, even high-performing people in corporate roles seem to not value competitiveness (against peers). Moreover, what we also noticed is that negative associations with competitiveness e.g. being ranked lower than others also leads to greater negative responses.

So, let’s sum up: the majority of employees at all levels of education and seniority do not value competitiveness over others but want to perform. So far so good. But there is a but. The but is that, as I already mentioned, there are also about 30% of employees who do value competitiveness highly, not to mention that of the remaining 70% few ranked it 0%, but just much lower than others needs, such as being valued in the workplace.

The question is does this 30% maybe rise through the ranks more so than others and therefore also be more likely to incorporate systems that promote competitiveness in organisations?

The answer to this question is not so clear because of a lack of research into trait competitiveness and leadership. However, other sources can give us indications. The first is that of the so-called dark triad that we mention regularly in these pages. The dark triad is Psychopathy, Machiavellianism, and Narcissism. All include putting oneself above others – and here we have much more research to draw on:

1% of the general population can be classed as psychopathic but in leadership positions this is 3-4%

Some sources report up to 20% of leaders having psychopathic tendencies (but also noting it may not necessarily be a bad thing)

Other academics have reported up to 50% of senior leaders falling on the dark triad scales

The numbers vary but we can clearly see that leaders are more likely to fall into these “dark” psychological profiles and some of these have been shown to correlate with lack of insight, and overconfidence. I have discussed some of these in other areas and it is not the main focus of this article. But it should be noted that these traits are not necessarily all negative and can give the necessary grit, determination, and a certain ruthlessness that may be necessary at senior levels. I did say “may”.

Positional Attitudes

A piece of research I wrote about here, though, interestingly, pointed to something else about personality and potentially toxic leadership, or harsh leadership at least. In this paper the authors manipulated a person’s feeling of power, i.e. authority, by getting them to rate others' behaviours in a business context and by changing their roles. Either being in a position of a lowly producer, or the position of a supervisor. What they discovered is that when people were in leadership positions, they judged other people’s failure to complete a business project (with justified excuses it must be noted) much harsher and were more willing to dish out punishment.

This is what the authors’ call a choice mindset, when we are in a position where we have more choice and control, we overestimate others’ ability to have choice and have control. This leads us to be overly critical of others. So, the position one is in, is more important than personality.

Similarly, research into people who win games shows they believe they deserve this. You may argue that if they win, they do deserve this. Sure, but with experiments conducted when chance was purely at play and the participants were informed of this e.g. being dealt a hand of cards (with no other play), or the roll of a dice, participants still believed they deserved to be the winner and overly assigned their own contribution to this (when they had no contribution to the outcome). So those who have had the fortune to win, be that in business, or other areas will over assign their own agency to this.

This is also forgotten in discussion of competitiveness – in most sports chance plays a large part (according to the research football and ice hockey are particularly influenced by luck). So even if we want to judge ability, which is fair, we may be judging outcome, or luck, and this will change one’s attitudes to this. If you’re on the winning end, you will think you deserved, it!

Now let’s look at what competitiveness can do to performance.

Competitiveness and Performance

First, let’s investigate if increasing the stakes drives performance. The standard logic is that if we increase stakes i.e. the reward, performance should increase. Let’s first look to a series of long-running experiments by Tom Wujec. You can watch this amusing and short TED talk. I have used the exercise successfully as fun and insightful task for leadership teams and business teams of all types. There is a focus on creativity and innovation which is his background, but that is another topic for another day. What interests us here, is what happened to output and creativity when the rewards were increased?

If you watch the video, you can see the humorous effect. When teams were offered a cash reward for producing the best (in this case the highest structure made out of spaghetti) in the time limit specified, performance plummeted across the board!

Yes, your read this correctly, but not only that, most teams actually failed to produce anything. In business terms this means that performance decreased and in many cases, output was zero. Not good. Very bad.

Now, you may wonder, why? Let’s understand this was in a time-controlled situation – and very tightly controlled i.e. they had 18 minutes to complete the task. It seems like the reward did motivate people, but the short time frame increased the stress and also increased disagreements in the team. Because reward was now on the line there was more on the line and so a lot of discussion and debate because they wanted to get the best result.

Similarly, insightful is another set of experiments conducted in India on cognitive performance. The one reason it was conducted in India is that simulating high rewards was much simpler and massively more cost effective i.e. it was possible to give rewards that would be spectacularly high and unfeasible in western countries. For example, a reward of $10 in some areas might be the equivalent of a week’s wages.

Again, what do you think happened in these experiments that were measuring cognitive ability i.e. participants were asked to solve cognitive problems and play cognitive games?

Yes, again performance dropped dramatically. Similarly, the stress of playing for a reward so large seemed to cognitively impair participants. However, small rewards improved performance. This seemed to provide the necessary ability to focus and engage in the task effectively without causing too much stress.

Now, this may sound counter intuitive. And Hollywood also has something to answer – how many times do we see situations where everything is at stake, saving the world, one’s life. The evil overlord who threatens constantly the lives of those who fail him (it normally is a him). These types of stakes are the biggest stakes possible.

But there is twist to this, and the creativity experiments give us some clues to this. As I said, if cash rewards were offered, performance dropped dramatically but if rewards were offered and preparation time given, then performance increased dramatically. So larger stakes with enough time to prepare can increase performance, and this is important to note.

It could also be that the type of reward is something that drives performance. A recent study into creativity and innovation in business and motivating the workforce to participate noted that giving a choice of rewards not only increased participation but the quality of proposals. This was conducted in a real-life scenario. The rewards on choice were 1. cash 2. discretionary (e.g. days off), and 3. donation to charity of choice. Rewards were given to those that were ranked in the top 20% of ideas submitted. Increasing the choice of rewards increased participation and quality of proposals.

But this study also highlighted some interesting further aspects. Namely that those people who were rated as most creative (they had undergone tests to measure creativity) seemed more motivated by the alternative rewards - particularly donating to a charity of their choice. Those that were less creative were more motivated by the cash! It seems that creative people aren’t just motivated by cash – what a surprise!

Another interesting aspect, I find, not mentioned by the authors in this study is that rewards were offered to those ideas that were in the top 20% rather than, say, the best, or top 5, or those that materialised into products, or cost savings. The reason this is interesting is that this gives everyone a fighting chance to gain some benefit whereas if single rewards are offered, it limits the people who enter because they may feel they have little or a low chance of winning. So, broadening the category of “winners” improved the inputs and quality of these overall. This highlights that the form of competition is important.

Winning in sport is not always about competitiveness

The above concept of broadening the category of “winners” is also something that some competitive people are against. It feels counter intuitive. To generate competition, we need to be competitive and stimulate this desire to be the single best. And yet this concept of broadening the “winners” seems to be a successful strategy in other areas namely in highly competitive sports and examples from some of the most successful and competitive sports teams also show this.

The thinking trap, and one that is particularly important for business and society, is that if you only need one good person, then you can focus on brutal competition, but if you need a lot of successful people and teams, as you do in business and for sports federations, then you may need to think differently (unless you have enough people to burn through and discard).

New Zealand Rugby and Norwegian Cross Country Skiing team are two examples of this. The former world-famed for the All Black rugby team classed as THE most successful sports team in history, really yes, an all time 77.4% since their first match in 1903. No other team comes close. The Norwegian cross-country team has come to dominate in cross country skiing being almost embarrassingly successful far outpacing previous close competitors, Sweden, Finland, Russia, and Germany. Podiums consisting of only Norwegian skiers are common – the top ten are normally majority Norwegian.

How did these two most successful of sporting nations do this? Inducting kids with high competitiveness from an early age? No, they do not! They do the opposite!

And they do the opposite for very good reasons. They also have more of an evidence-based approach rather than a gut feeling, intuitive approach. Both are small nations, and both realised that the key to getting successful adults sports teams was getting high participation, and keeping this participation high. Ruthless competition and heavy filtering young in life massively reduces participation and does not allow kids to develop. They also had a more refined approach, for example, they know that kids develop at different paces and sometimes early “talent” selection is not selecting talent but only those who mature earlier.

Without going into the details here, both countries have well-structured programmes that enable kids to engage and keep engaged and level the playing field. The type of thing that highly competitive people intuitively feel is wrong. The Norwegian cross-country skiers don’t have ranked races until after they are 14 years old! Does this limit the number of competitive skiers, or weaken their competitive bite? Absolutely not! It enables the country to develop more high-quality skiers than any other nation, and then enables them to get really competitive later on. And competitive they are - and incredibly successful also.

To translate this into business it is about enabling a larger part of the population to be competitive when their skills have developed. And the analogy is apt for business because as in the case with the creativity proposals, the more people who engage, the higher the quantity and quality of the input, and therefore later, the output.

Individual Rewards

But back to rewards and team performance. It has been noted in many places that everything that happens in businesses, happens in teams. Particularly in the modern interconnected world. I will speak about inter-brain synchrony in the next article but for now let’s look at what the impact individual or team-based rewards had on team performance.

Van Bewel has conducted experiments over the years on inter-brain synchrony but also on team performance. In a series of recent experiments, he and his fellow researchers looked at how brains synchronised and how task and rewards impacted this and impacted performance. In these type of experiments teams have to solve problems collectively or produce something collectively.

These groups of four were then given the motivation of a collective reward or an individual reward if they performed better than other individuals. Which produced the best results? Clearly the team situation. What is also of interest is they also had a hybrid version whereby 20% of one’s own individual reward could be donated to a group pot and split between participants and if all participants donated the pot would be doubled. This proved to be motivating. This showed that contributing to the “greater good” was also beneficial.

There was one task, however, where individual performance was better, and this was a typing task – which doesn’t benefit from teamwork, and collaboration simply slows down the process. This does show that some tasks will benefit from individual work and may be best suited to individual rewards – but this is limited. As I said much of what happens in business is collaborative.

Uncertain Rewards

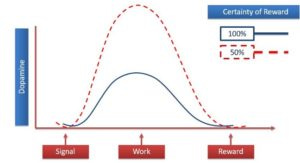

Another clue to how competition can positively affect behaviour is the fact that uncertain rewards are more motivating than certain rewards. This is directly related to release of dopamine – which I have outlined is more to do with motivation than reward (or rather encoding importance). Dopamine release is highest when rewards are uncertain but, intriguingly, to a probability of 50/50. Or translated into everyday language of having a “fighting chance”, oh that’s a competitive word, a “realistic chance”, of getting the reward.

This 50/50 probability is interestingly precisely what we see in many sports finals with two teams or individuals competing for the main prize. It also goes against the logic of reinforcement learning whereby we should get a reward each time we successfully complete a task. We are actually more motivated when we don’t get a reward all the time (something video game developers know very well).

The Competitive Brain

Of course, we would also like to know what is happening in the brain during competition and with those competitive types. A further question is, is this beneficial and, importantly, under what conditions?

Unfortunately, there hasn’t been much research into trait competitiveness and the brain - neither of the brain in competitive situations. One piece of research did put rats into a competitive situations and measured neural response. These rats were put into two different situations and their brains’ responses measured. One, they had to find a small reward independently and two, they had to try to get a large reward but with a “competitor”. In the competitive situation the rat’s ACC, which I review here, was more active. This could be because of internal judgement of personal status against the other rat i.e. am I likely to win or lose?

Another aspect that has been noted is that of so called “warriors” or “worriers”. The warriors being the more dominant “go get it” type of personality and this has been related to dopamine and stress responses. The worriers becoming overloaded and stressed more quickly while the warriors can stay calm and fight it out and are more resilient to stress. The gene COMT V158M has been identified controlling these types through its modulation of dopamine in the prefrontal cortex.

Similarly, and related to the above, are so-called BAS types (Behavioural Activation System) again “go getters”. These show greater left prefrontal activation that is associated with motivated action but also more individualistic action. Indeed, left hemisphere activation has been associated with approach behaviours, planning, and strategy. I review these in the above article “Of Carrots and Sticks”

We can also see when we revisit the SCOAP model that that we can relate this to the facets of SCOAP. Under “S” we can see that social status is often given or increased if winning competition, and information on competition gives greater Orientation of what is needed to succeed.

Social Darwinism

Now a brief step back to our ultra-competitive types or those who are on the scales of the various dark triad syndromes. There is something called social Darwinism. This is the concept that life is driven by the “survival of the fittest”. We are programmed to fight it out amongst each other with only the winners surviving to procreate. Similarly weakening this gene pool will turn us into softies that are unable to deal with the toughness of life.

Social Darwinists, for example, would feel that enabling kids to have fun in their cross-country ski training and to have unranked races will destroy competitiveness: you are not tapping into natural competitive instincts because we are born to outcompete others. Social Darwinists have less empathy and a lower sense of fairness. Life is tough not fair.

In fact, a recent study into Social Darwinists quoted that they were more likely to:

“…display admiration for power, a desire to dominate, a desire to pursue their goals at all costs, and hostility. They were also more likely to have low self-esteem, low self-sufficiency, and a fearful attachment style in their close relationships.”

The thinking mistake, and misunderstanding of evolutionary principles, here is in thinking that survival was always about the individual – this is not the case. As a tribal species, survival was always about the survival of the group and so if we do indeed focus on evolutionary theory, which I do a lot, for business, we should be talking about collaboration for the benefit of the group. This is how evolution designed our brains and bodies and why we have desire for attachment and why we tend to operate best in groups.

But there is competition!

Yes, indeed. And this is where we need to find nuance.

Having competitors does enable you to pull out the best in each other. It gives clarity and focus. Competition is good. Indeed, we also see this in the sports field of top competitors pulling the rest of the field along and enabling higher average performances. So, this is also not to be underestimated. Indeed, some research has shown that those high in trait competitiveness thrive in competitive environments and roles, notably in sales.

What I am arguing for here is understanding the nuance and where to put the focus. Most business are looking for collaborative high-performance and so individual competitiveness may hinder and derail this. Aligned focus on beating the market is good.

Summary

So, we can see that we have to be very careful with the concept of competition. It is not that we are not motivated by competition, but that this can derail many of the collaborative processes in business and thereby produce lower quality, lower output, and increase stress and well-being of multiple people in the organisation.

In Summary

Team rewards promotes team operation (but the team must be a size that people can meaningfully contribute)

Small rewards are motivating and minimise a stress response

Alternative rewards are motivating

Individual rewards with meaning (e.g. contribution to others) can be effective

Multiple rewards are better than one big reward

Some contexts and situations may benefit individual rewards and individualisation

Some people, however, will respond to individualisation more strongly than others

Social Darwinists can disrupt atmosphere

Benchmarking rather than social comparison

But also

Competition does focus the mind

People high on trait competitiveness like to compete – give them opportunities to do so

Certain roles may also be suitable to and benefit from a competitive environment (e.g. sales)

So, I am not arguing against competition. As many of you know I am a competitive sports person. I am just arguing for being much more mindful in how, what, and when, we add competition into the business environment. We do need to have high-performing teams and we do have competition. But this is precisely it – it should be externally focused and not internally. Clear, well-thought-out reward systems that reward teams and individuals and think carefully about those rewards so that they are fair and meaningful, and enable teams to perform to their best, will increase quality and output for organisations.

References

Dark Triad

Ahmad, H., Arif, A., Khattak, A. M., Habib, A., Asghar, M. Z., and Shah, B. (2020). Applying Deep Neural Networks for Predicting Dark Triad Personality Trait of Online Users. in International Conference on Information Networking doi:10.1109/ICOIN48656.2020.9016525.

Furnham, A., Richards, S. C., and Paulhus, D. L. (2013). The Dark Triad of Personality: A 10 Year Review. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 7, 199–216.

Furtner, M. R., Rauthmann, J. F., and Sachse, P. (2011). The Self-Loving Self-Leader: An Examination of the Relationship Between Self-Leadership and the Dark Triad. Soc. Behav. Personal. an Int. J. 39, 369–379.

Giammarco, E. A., and Vernon, P. A. (2014). Vengeance and the Dark Triad: The role of empathy and perspective taking in trait forgivingness. Pers. Individ. Dif. 67, 23–29.

Kaufman, S. B., Yaden, D. B., Hyde, E., and Tsukayama, E. (2019). The light vs. dark triad of personality: Contrasting two very different profiles of human nature. Front. Psychol. 10. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00467.

Muris, P., Merckelbach, H., Otgaar, H., and Meijer, E. (2017). The Malevolent Side of Human Nature: A Meta-Analysis and Critical Review of the Literature on the Dark Triad (Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and Psychopathy). Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 12. doi:10.1177/1745691616666070.

Paulhus, D. L., and Williams, K. M. (2002). The Dark Triad of personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. J. Res. Pers. 36, 556–563.

Veselka, L., Giammarco, E. A., and Vernon, P. A. (2014). The Dark Triad and the seven deadly sins. Pers. Individ. Dif. 67. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2014.01.055.

Volmer, J., Koch, I. K., and Göritz, A. S. (2016). The bright and dark sides of leaders’ dark triad traits: Effects on subordinates’ career success and well-being. Pers. Individ. Dif. 101. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.046.

Competitive Brain

Balconi, M., Crivelli, D., and Vanutelli, M. E. (2017). Why to cooperate is better than to compete: Brain and personality components. BMC Neurosci. 18. doi:10.1186/s12868-017-0386-8.

Balconi, M., and Vanutelli, M. E. (2017). Brains in competition: Improved cognitive performance and inter-brain coupling by hyperscanning paradigm with functional near-infrared spectroscopy. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 11. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2017.00163.

Hillman, K. L., and Bilkey, D. K. (2012). Neural encoding of competitive effort in the anterior cingulate cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 15. doi:10.1038/nn.3187.

Sinha, N., Maszczyk, T., Zhang, W., Tan, J., and Dauwels, J. (2017). EEG hyperscanning study of inter-brain synchrony during cooperative and competitive interaction. in 2016 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, SMC 2016 - Conference Proceedings doi:10.1109/SMC.2016.7844990.

Wang, Y., Wei, D., Li, W., and Qiu, J. (2014). Individual differences in brain structure and resting-state functional connectivity associated with Type A behavior pattern. Neuroscience 272. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.04.045.

Contextual responses

Slabu, L., and Guinote, A. (2010). Getting what you want: Power increases the accessibility of active goals. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 46, 344–349.

Wang, G., and Netemeyer, R. G. (2002). The Effects of Job Autonomy, Customer Demandingness, and Trait Competitiveness on Salesperson Learning, Self-Efficacy, and Performance. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 30, 217–228.

Mario D. Molina et al. It’s not just how the game is played, it’s whether you win or lose.Sci. Adv.5,eaau1156(2019).DOI:10.1126/sciadv.aau1156

Reward

Depue, R. A., and Collins, P. F. (1999). Neurobiology of the structure of personality: Dopamine, facilitation of incentive motivation, and extraversion. Behav. Brain Sci. 22, 491–517. doi:10.1017/S0140525X99002046.

Fiorillo, C. D., Tobler, P. N., and Schultz, W. (2003). Discrete coding of reward probability and uncertainty by dopamine neurons. Science (80-. ). 299. doi:10.1126/science.1077349.

Krusemark, E. A. (2018). “Physiological reactivity and neural correlates of trait narcissism,” in Handbook of Trait Narcissism: Key Advances, Research Methods, and Controversies doi:10.1007/978-3-319-92171-6_23.

Reinero, D. A., Dikker, S., and Van Bavel, J. J. (2021). Inter-brain synchrony in teams predicts collective performance. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. doi:10.1093/scan/nsaa135.

Sinha, N., Maszczyk, T., Zhang, W., Tan, J., and Dauwels, J. (2017). EEG hyperscanning study of inter-brain synchrony during cooperative and competitive interaction. in 2016 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, SMC 2016 - Conference Proceedings doi:10.1109/SMC.2016.7844990.

Vechetti, I. J., Peck, B. D., Wen, Y., Walton, R. G., Valentino, T. R., Alimov, A. P., et al. (2021). Mechanical overload-induced muscle-derived extracellular vesicles promote adipose tissue lipolysis. FASEB J. 35. doi:10.1096/fj.202100242R.

Zhou, J., Oldham, G. R., Chuang, A., and Hsu, R. S. (2021). Enhancing employee creativity: Effects of choice, rewards and personality. J. Appl. Psychol. doi:10.1037/apl0000900.

Positive competitiveness

Bronson P, Merryman,A (2013) Top Dog: The Science of Winning and Losing, Twelve, New York

Brown, S. P., Cron, W. L., and Slocum, J. W. (1998). Effects of Trait Competitiveness and Perceived Intraorganizational Competition on Salesperson Goal Setting and Performance. J. Mark. 62. doi:10.1177/002224299806200407.

Cahlíková, J., Cingl, L., and Levely, I. (2020). How stress affects performance and competitiveness across gender. Manage. Sci. 66. doi:10.1287/mnsc.2019.3400.

Reese, Z. A., Garcia, S. M., and Edelstein, R. S. (2022). More than a game: Trait competitiveness predicts motivation in minimally competitive contexts. Pers. Individ. Dif. 185. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2021.111262.

Schrock, W. A., Hughes, D. E., Fu, F. Q., Richards, K. A., and Jones, E. (2016). Better together: Trait competitiveness and competitive psychological climate as antecedents of salesperson organizational commitment and sales performance. Mark. Lett. 27. doi:10.1007/s11002-014-9329-7.

Articles

Psychopathic leaders: https://www.cnbc.com/2019/04/08/the-science-behind-why-so-many-successful-millionaires-are-psychopaths-and-why-it-doesnt-have-to-be-a-bad-thing.html

The Surprising Truth of Why Powerful People can be Toxic https://andyhab.medium.com/andys-quick-hits-33-the-surprising-truth-of-why-powerful-people-can-be-toxic-dce7ba460a8b?sk=912e076b2b5c081ca59b53d783585e81