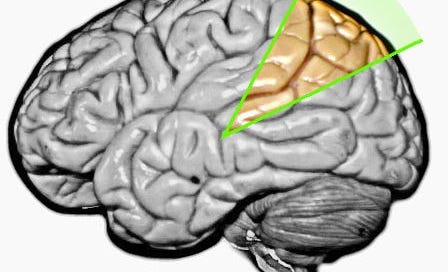

The height of the 10% of the brain myth probably came with the film Lucy In 2014. In the film the heroine Lucy is smuggling illicit party drugs in her stomach when, after a kick in the stomach, one of the bags breaks and she is involuntarily given a hefty dose of this new drug which we are told is naturally released by mothers and helps their children’s growth and brain development.

This enhances her cognitive ability and gives her telekinetic insight— after then taking a further intentional mega dose from the remaining bags in her stomach, her cognitive abilities expand slowly edging towards the elusive 100% whereupon she becomes one with the cosmos. Cute. Nice. Attractive film making. And junk.

The film received general positive review even though many know it is based on a myth. The myth has been with use for many years and is also very enduring also because of its inherent positive spin: “You can release your potential and you too can become a genius!”

…we do have brain plasticity, changeability, and we can develop our brains — some of the ways to do this are a lot simpler than we may assume.

The myth is fundamentally wrong, but, before you call me a party pooper, there is hope because we do have brain plasticity, changeability, and we can develop our brains — some of the ways to do this are a lot simpler than we may assume. In fact in children’s education some of the things we have stopped doing are some of the most important.

History of the Myth

Wikipedia gives a comprehensive view of the history of the myth which has unclear origins. It is generally ascribed to William James, the father of modern psychology, who wrote in the 1880s that we use but a fraction of our potential. Dale Carnegie the legendary author of “How to win friends and influence people”, considered one of the first self-help books and forerunner to the human potential movement, stated in his foreword, falsely, that William James had quoted we only use 10% of our potential. The seed was planted and this propagated further and became entrenched in the human potential movement and standard stock for motivational speakers.

Biological underpinnings.

There also appeared to be some justification in this respect when first uncovering the biological secrets of the brain in the early years of the myth:

Firstly, there seemed to be vast amounts of neurons many of which couldn’t be ascribed any function (we now know a lot more about these).

Secondly, there were also vast quantities of so-called glial cells without any clear function (we now know that these support neurons and feed them nutrients and do all sorts of housekeeping work in the brain).

Thirdly, the cases of autistic savants or individuals who after brain injury discover incredible abilities, such as the man who after a concussion could miraculously play the piano, also lend support to this myth.

So how much of the brain do we use?

How much do we use?

The simple answer is 100% all the time. Unfortunately for the motivational speakers. As living cells all brain cells need to be active otherwise they will die — but their activation and stimulation depends on many factors.

Firstly, it will depend on input — input defines what gets activated. Secondly, on carrying out actions.

Most of the brain is used for what are considered unspectacular functions by us human beings. The brain, for example, needs to use incredibly complex patterns of activity to walk down the street or climb the stairs. Which is why walking is one of the simplest and most effective ways to activate your brain and stimulate brain growth.

See my medium article here on this.

In short when you do nothing your brain is very active and very interconnected

So in short the brain dedicates a lot of resources to things we don’t even consider as complex — what we human beings are thinking of when we say release our potential is not the ability to walk across uneven ground (or, even more complex, run across uneven ground) but in cognitive ability: playing chess, managing social interactions, dealing with complexity, learning languages, academic achievement, innovation, and inspiration.

Now each of these uses different sets of structures in the brain, so building one set of skills may not, and mostly doesn’t, transfer to other skills. Research into cognitive training shows this. Training certain skills makes you better at these skills. So far so good. But they rarely transfer to other skills. Bummer. And far transference, which is when cognitive skills transfer to wide and reaching abilities are almost zero. Big bummer.

Another conundrum is that though we think your brain should be most active when we engage in complex cognitive tasks this is not the case:

Tasks such as walking, or gardening, or baking, may take up many more resources (yes, so do them).

But even more interesting was, at the time at least, the discovery of the default mode network. This is the brain activity you have when you are doing nothing. So sit down close your eyes, and try to think of nothing (you will, of course, think of something). Your brain will enter into default mode network. But the default mode network is an incredibly active state. You brain will have a hum of activity connecting various brain regions — which is why your brain wanders and thoughts pop out and in to your mind’s eye.

In short when you do nothing your brain is very active and very interconnected — which is why it’s great for innovation and creativity and problem solving. It allows your brain to connect diverse ideas. So by doing nothing you may be doing more!

Ok, so that leaves us with

The brain is very active when doing what we consider simple mundane tasks

The brain is very active when we are “thinking” of nothing

Training specific tasks rarely has far transfer to general abilities

But surely, I can hear you say, we can develop our ability?! We now know the brain is plastic (and have done for more than half a century actually) — surely we can release more of our potential and rewire our brains?!

Our brain is designed to adapt to the environment around us and the activities we regularly do through its inherent plasticity

Well, of course we can, but let’s keep both feet on the ground

How much of the brain can we develop?

Of course, we can develop our brain and become better at things, release our potential in the language of motivational speakers (of which I am sometimes classed).

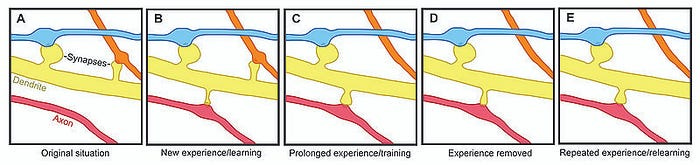

We tend to be amazed that playing the piano grows the brain, and that playing computer games changes the brain physically. But this is true for any activity; sewing, playing football, practicing theatre, writing a novel… All of these change the brain. Our brain is designed to adapt to the environment around us and the activities we regularly do through its inherent plasticity. Everything you do that is new will “rewire” your brain.

This is not different to other cells in our body (such as muscles) that adapt to different inputs and outputs. So, doing new activities will grow certain areas of your brain by building new connections between these neurons and strengthening certain pathways.

The level of this growth depends on:

Age — there are critical phases of development this is just why exposure to different and varying stimuli is essential to healthy development of children

Intensity of activity and new stimulus — the stronger the intensity, by effort or emotionality the more likely it is to stimulate growth

Habituation — the brain will also habituate to repetitive input and stop responding with time

Genetics — just like in building muscles some of us are more predisposed to plasticity than others. It’s just the way it is. Sorry.

To summarise: though plasticity is different at different ages, and in different people, we can all improve our abilities. In whatever area that is. The degree and speed to which we improve our ability will be defined by factors that we can’t control (but that shouldn’t mean we shouldn’t keep trying).

The Stuff that Really Activates Our Brain

What may be more surprising, to some at least, is that activities that are most demanding and beneficial are sometimes not taken so seriously. In schooling we consider what subject and concepts we should be teaching in early years, separate classes into age groups and drip feed subject matter to children. Yet, from a brain development viewpoint, much of this makes no sense. Yup, I did say that. It’s not the best thing for the brain when we think of holistic brain development and development of advanced cognitive abilities.

The activities that stimulate the brain most are activities such as playing. Playing requires vast networks that control complex behaviours and decision making: abstraction, imagination networks, social judgment, pre-empting decisions and choices of others, language, emotional control, role playing, and so on and so forth, all of which are very advanced brain functions using vast and complex networks and stimulating development of these.

If there is one piece of advice for brain growth, it is not to put children into a series of intense training at an early stage but give exposure to as much as possible and let them play!

It is just as important to note that rest is just as important as stimulation. Brain growth happens mostly during sleep, and down time which enables detoxification of the brain and rebalancing of natural wave patterns. So you can practice all you want but if you skimp on sleep you will be limiting your ability to grow your brain. So, more stimulation is not necessarily better!

Getting the balance right is essential — stimulation plus rest and sleep.

Growth mindset

A final note is that of mindset. And this is where using a version of the 10% myth is beneficial. But it should be in terms of what I have outlined above believing in the ability to improve or grow and not seeing ability and skills as fixed.

The term Growth and Fixed Mindset was proposed by Caroline Dweck in her famous book Mindset: The New Psychology of Success in 2006. Simply she outlined two mindsets (it is simplified of course): those that see the ability to grow (growth mindset) and those that see many things as fixed (fixed mindset) including abilities. Those with growth mindset were better able to adapt learn and improve their abilities. She sees this as one of the most critical factors in education. I tend to agree through I know the research paints a more nuanced picture.

Similarly, we also know that teaching kids about neuroplasticity, the ability of the brain to grow as I have outlined, has been shown to be beneficial. This is particularly beneficial, notably, and particularly, in children classed as “at-risk”. This is important because this enables those underprivileged kids to have a belief in themselves and take on the world and improve their lot.

Summary

So, in summary we always use all of our brain, but we can improve brain performance through practice and exposure to new stimuli. We should continue doing this throughout our lives to keep our brains healthy and functional. And definitely we would all be well advised to exert effort to use more of our potential — we may surprise ourselves at how much we can do!

Children will go through different phases of growth and we should encourage exposure to different stimuli but underrated activities such as play are exceptionally important to brain development.

Do use 100% of you brain to do the right thing for yourself and also your children. And that includes sleep and play!